The recent murder of Ahmaud Arbery in Brunswick, Georgia, brings to mind the ugly history of lynching in America. Bryan Stevenson, founder of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), defines lynching as "a racially motivated act of violence committed by two or more people where there is no accountability." Lynchings were brutal acts of torture, often in public, designed to terrorize black people. State and federal officials generally looked the other way. EJI has documented more than 4400 lynchings of black people in the United States between 1877 and 1950.

Lynching was often justified as being a necessary response and deterrent for the crime of rape against white women by black men. Pioneering investigative journalist Ida B. Wells began to question this justification when a personal friend, Tommie Moss, was lynched for defending his grocery store against attack by a white mob in 1892. She began to investigate lynchings, poring over records and going to the locations where they happened to interview people involved. Mia Bay, editor of a collection of Wells' works, writes, "In a fateful May 21 editorial in Free Speech, Wells contended that lynching had nothing to do with rape or the defense of white women, whose relationships with black men were often consensual. Instead, it was a form of racial terrorism designed to reinforce white political and economic power in the South, and usually targeted blameless victims such as Moss, McDowell, and Stewart."

Wells spent the rest of her life researching, writing about, and denouncing lynching. Her pamphlets Southern Horrors and The Red Record were examples of her groundbreaking investigative journalism for which she won a posthumous 2020 Pulitzer Prize. On speaking tours in Britain, she gained international support for her anti-lynching campaign. Her career in journalism, speaking, and organizing helped to turn public opinion against lynching. When Wells died in 1931, lynching rates were declining significantly, but they didn't disappear altogether.

While the form is different, every time an unarmed black person is killed and the perpetrators go unpunished, the legacy and trauma of lynching is brought back to the surface. Stevenson notes, "Our nation continues to underestimate the painful burden that has been placed on black people and the traumatic injury we continue to aggravate when our justice system refuses to hold accountable perpetrators of unnecessary violence if they are white and invoke some public safety defense."

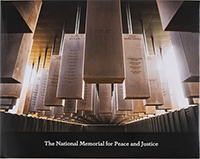

As Christians, we understand that confession is a necessary step to repentance. 1 John 1:9 says, "If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just and will forgive our sins and purify us from all unrighteousness." Telling the truth about our history and our present injustices is a necessary step towards healing and reconciliation. Equal Justice Initiative has taken up the mantle of truth-telling about our nation's history of lynching. On April 26, 2018, EJI opened The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, the nation's first memorial dedicated to the legacy of enslaved black people, people terrorized by lynching, African Americans humiliated by racial segregation and Jim Crow, and people of color burdened with contemporary presumptions of guilt and police violence. Their report, Lynching in America: Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror, records a history that all Americans should know and understand.

Lynching in America states, "Decades of racial terror in the American South reflected and reinforced a view that African Americans were dangerous criminals who posed a threat to innocent white citizens. Although the Constitution's presumption of innocence is a bedrock principle of American criminal justice, African Americans were assigned a presumption of guilt." This presumption of dangerousness and guilt still lingers today. Until we fully understand this and set out as a nation to change this false narrative, we will continue to experience cases like the murder of Ahmaud Arbery that traumatize our African American brothers and sisters.